Rosario Rivera-Bond or The False Naiveté

by Marc Jimenez

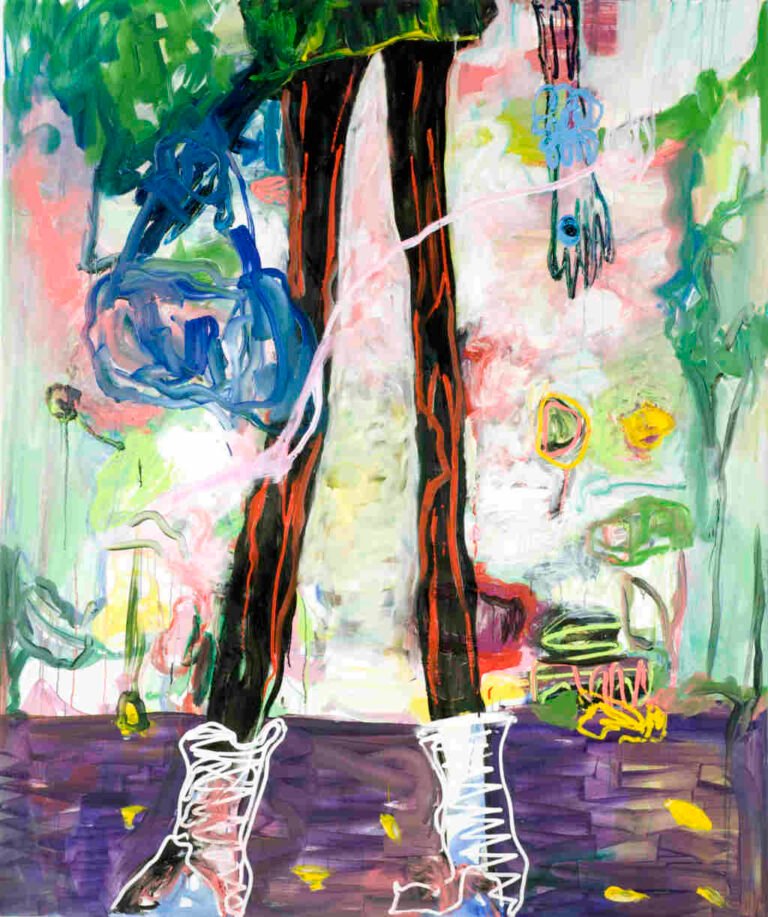

Is it possible that the spirit of the Grande Chaumiére, where Rosario Rivera-Bond once had a residency, continues to intensely inspire her work? We are tempted to believe so, as her canvases vibrate with the faraway presence and ephemeral inhabitants of that institution. Alberto Giacometti mainly comes to mind, but mostly one thinks of Paul Rebeyrolle, painter of apocalypses, catastrophes, and savage liberty who was more akin to the Baselitz generation and mixed, ground, and worked his medium and until it devoured his canvases. This expressionistic position, or rather, this affiliation with the neo-Fauvists, is found in the work of Rosario Rivera-Bond. It is visible in her vivid use of color and in the state of mind projected in her work. Sometimes happy, sometimes melancholic, there is a medium between joy and sadness that translates through most of her work. The pictorial gesture found in Rivera-Bond’s work makes one think of the myth of Butades of Sicyon, who in ancient times discovered the medium of painting through his daughter, often referred to as “The Maid of Corinth”, after she traced the outline of her lover’s face upon a candlelit wall. In the work of Rosario Bond, however, the history of the portrait is turned on its head. There is no evident relation between the disappearance of the human face in her paintings of 2008 or in the extinction of the figure in the recent series All My Friends (2009), and the celebrated academic and neoclassical works of Jean-Baptiste Regnault (1754-1829). The ancient myth of the origin of painting is completely changed; the figure seems to have dissipated, diluted in the canvas and using paint as its only sustenance. The vanishing of the face—its almost nonexistent—is excessive and anguished in her latest works where one can barely make out a forehead, a pair of eyes, a nose (see All My Friends IV). These all appear as sketches in the paintings of a year ago, and in a very different form, alternating de-figuration with pure and simple disappearance. Mackled and scratched in Bunny Girl, a grotesque caricature in Nurses in Love and in The Happy Couple, the face is totally absent in Golf in High Hells and in an evocation reminiscent of Giacometti, the lengthened face, is the star of the seventies, Twiggy. These allusions, gently ironic and at times satirical and humorous, appear every so often in a manner and style that serves to direct our gaze in the direction of Neo-Expressionism, the free figure, or towards “bad painting”. It’s hard not to think of the humorous yet serious and impertinent anecdotes of Robert Combas, the brilliant, illustrative, and modest universe of Hervé di Rosa, or the indecipherable and comical portraits of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Rosario Bond’s painting can’t be reduced simply to these comparisons. It is impossible to discover a direct nexus between the previously mentioned artists and the boundless imagination and Caribbean fantasy of this artist, originally from the Dominican Republic and who studied architecture and interior design at the Universidad Nacional Pedro Enriquez Ureña.

Long after the era of ekphrasis, the minute descriptions of consciously unfinished enigmatic portraits and as such, are hieroglyphics that are hard to interpret on first sight; a deeper narrative reveals the coherence of a work much less innocent and frivolous than it appears. This is how Rosario Rivera-Bond’s world of personal myths opens itself up to the world and what is depicted is a consumer society—with its clichés, ostentatious luxuries, and stereotypical fashion addicts (high-heels, lipstick). It’s a world about distractions, image, and the condition of women caught between reality and fantasy, precisely at the point where the everyday takes on the aspect of a capricious, fantastic universe. The burlesque in the situations stigmatized by Bond fool no one. Naiveté cannot be taken for face value in Bond’s work. The artist settles on showing the viewer a contrasting sense of humor from one canvas to another. If Teddy Bear’s Friends have sympathetic and happy faces, then The Happy Couple isn’t particularly happy or agreeable, nor is the Nurse in Love, who is apparently caught in a full-on emotional crisis. The feigned innocence in which Rosario Bond seems to take pleasure in pokes fun at the defects and obsessions of our time with a subtle mix of irony and parody. Her work slyly reflects a cruel and acerbic critique of our modern times. Without a doubt, the pictorial fiction in Bond’s paintings carries with it a paroxysm of non-reality and continues to be one of the most privileged media in that what is real is perceived and transfigured through the prism of an inventive and subjective curiosity. Rosario Bond seems to share this conviction, creating very personal poetry and generous paintings, free of the coercive whims of the art world, namely the salesmen, spectators, gallerists, and dealers. The Grande Chaumiére was coined “the free academy” for generations, and there is no doubt that Rosario Bond has stayed true to its governing principle.

November 13, 2009 Miami